IDE-Bench

Evaluating Autonomous Agents in Realistic Software Environments

We are releasing IDE-Bench, a multi-language, full-stack benchmark designed to evaluate Large Language Models (LLMs) acting as autonomous IDE agents. IDE-Bench assesses an agent's ability to navigate, reason, and modify complex repositories using the same tools available in modern AI-native IDEs.

Over the past year, AI-assisted programming has transformed from simple autocomplete to autonomous loops: reading files, searching codebases, running tests, and iterating until convergence. However, existing benchmarks often test models on their abilities to complete tasks resembling single-function generation, static context retrieval, or terminal execution without the tool usage an IDE offers. Thus, we have built IDE-Bench, designed to evaluate LLMs as IDE agents, embedded inside repositories, provided with the same tools and resources used in autonomous IDE agents.

The Shift to IDE Agents

IDE Agents go beyond "code generators," acting as systems that can utilize tools to understand and modify a codebase. To succeed in IDE-Bench, models must:

grep -rUse semantic search and grep to locate relevant logic across files

cat -nRead file contents with specific line-range controls

sed -iApply structured edits to the codebase

./testRun terminal commands and self-generated tests to validate work

Our Dataset

IDE-Bench consists of 80 tasks across 8 repositories evaluating models' performances:

Command-line tool for managing eSIM devices with C string/memory handling, file parsing, and core command implementations

Webhook/event notification system focusing on async control flow, retries, and delivery tracking

Memory profiling/leak detection toolkit with allocation tracking, leak detection logic, and report generation

Code-quality metrics and reporting with parsing, metrics computation, and validation

Full stack document translation app spanning backend/API, databases, authentication, and UI

Game engine components with animation, physics, rendering, and math-heavy features

Network log analysis scripts covering TCP/UDP parsing and bandwidth/anomaly metrics

Java web application for monitoring smart hub devices with routing and service-layer logic

Example Task

Let's walk through an example using Task 4 from the Event Callback System, which asks the model to implement a fix to correctly rate limit user requests. The Event Callback System enables external services to subscribe to application events and ensures that notifications are delivered reliably, securely, and with full visibility.

task_description: |

Task: Event Notification Delivery Platform - flow-throttle audit

Instructions:

Rate limit analysis is essential for monitoring API usage and understanding request patterns. This task is to fix a calculation bug in a rate limit analyzer that processes request records.

We have a script at `scripts/rate_limit_analyzer_cli.ts` which is broken and needs to be fixed. The script analyzes rate limit request records and calculates statistics for each endpoint.

Goal:

- Process request records from a JSON file

- Calculate total requests per endpoint

- Calculate allowed and blocked request counts

- Calculate average success rate (allowed / total) correctly

- Output results in a specific format

Input:

- Command line arguments:

- Required: path to JSON file containing request records

- JSON file format:

```

[

{"endpoint": "/api/users", "timestamp": 1234567890, "status": "allowed"},

{"endpoint": "/api/users", "timestamp": 1234567891, "status": "blocked"},

{"endpoint": "/api/orders", "timestamp": 1234567892, "status": "allowed"}

]

```

Example records:

"{\"endpoint\":\"/api/users\",\"timestamp\":1234567890,\"status\":\"allowed\"}"

"{\"endpoint\":\"/api/users\",\"timestamp\":1234567891,\"status\":\"blocked\"}"

"{\"endpoint\":\"/api/orders\",\"timestamp\":1234567892,\"status\":\"allowed\"}"

"[]"

- Each record must have endpoint, timestamp, and status fields

- Status must be either "allowed" or "blocked"

- Empty arrays should be handled gracefully

Output:

- Printed to stdout:

```

Endpoint: /api/orders

Total: 1

Allowed: 1

Blocked: 0

Average: 1.00

---

Endpoint: /api/users

Total: 2

Allowed: 1

Blocked: 1

Average: 0.50

---

```

- Endpoints sorted alphabetically

- Average represents success rate (allowed / total)

- All decimal values formatted to exactly 2 decimal places

- Empty file outputs nothing (no endpoints)

Constraints:

- Script must not crash on empty JSON arrays

- Script must not crash on invalid JSON

- Average calculation must be correct (allowed / total, not allowed / (total - 1))

- No extra debug or logging output to stdout or stderr

- Output must match the expected format exactly

- Endpoints must be sorted alphabetically

What will be Tested:

- Basic statistics calculation is correct

- Multiple endpoints are processed correctly

- Average success rate calculation is accurate

- Empty JSON array is handled gracefully

- Invalid JSON is handled gracefully

- Output format matches exactly

- Endpoints are sorted alphabetically

- Decimal precision is exactly 2 places

- No debug output to stderr

- Mixed allowed and blocked requests are counted correctly

difficulty: easy

category: Bug

tags: [typescript, webhook, rate-limiting, analytics]

parser_name: pytestWhy These Tasks Are Difficult

The difficulty comes from the friction that engineers and autonomous agents in IDEs face daily including underspecification, multi-file dependencies, brittle specifications, and hidden constraints. One recurring theme across these tasks is the difficulty for models to get from “mostly correct” to “fully correct.” This becomes important when evaluating agent behavior, as they are often expected to complete tasks extremely precisely.

Our Harness

The core of IDE-Bench is a sophisticated evaluation harness designed for reproducibility and realism.

.png)

IDE-Bench Workflow: We first launch a dockerized container and parse the task descriptions. The agent utilities module is responsible for spinning up the LiteLLM harness runtime within the container, and the output is passed into the grader system, which utilizes the diff verification system to parse outputs.

15 tools available for IDE agents

codebase_searchKeyword search across the codebase to find files or lines of code

grep_searchRegex-powered search for more complex patterns than those found in codebase_search

file_searchFinds files by name or path pattern when the path is unknown

list_dirList the directory structure to find possible entrypoints

read_fileOpen and read the given file

write_fileCreate a new file or rewrite a file with given contents

delete_fileRemove a file

run_terminal_cmdRun shell commands such as builds, self-created tests, and scripts; includes support for longer-running processes

api_callSend an HTTP request to test and validate REST API behavior

database_queryRun MongoDB operations, such as find, insert, update, delete, and aggregated, to confirm the app's data is being stored and returned correctly

edit_notebookunusedModify Jupyter notebook cells; supported by harness, but not used by the 80 tasks

web_searchrareSearch the web for documentation and examples; supported by harness, but used very seldom in the 80 tasks

create_diagramCreate a Mermaid diagram to visualize flows

ui_testAutomate browser interactions to test frontend features such as click, type, navigate, screenshot

websocket_testTest Socket.IO and WebSocket real-time features by connecting the client and sending and receiving

Experiments & Results

We evaluate 15 frontier and open-weight models on IDE-Bench using both pass@1 and pass@5 metrics. We see a clear stratification across the models; first there is a small frontier tier led by GPT 5.2 (95% pass@5), followed by Claude's models and GPT 5.1 Codex Max, ranging from 85 to 88 pass@5 rates. However, even these strongest models fail to solve all tasks, indicating a non-trivial ceiling.

On the other hand, open-weight and smaller models exhibit much lower success rates, often failing to resolve tasks that require longer multi-file reasoning or repeated refinement.

Importantly, we see a variance in the improvement rates from pass@1 to pass@5 across models; models below the 85% threshold improve by much larger amounts (e.g. DeepSeek V3.2 31.25% → 71.25%). This 85% threshold appears to mark a transition where models shift from inconsistent behavior to stable, first-attempt success. Sonnet 4.5 leads first-attempt pass rate at 87.5%, followed by GPT 5.2 (85%) and Opus 4.5 (83.75%). For deployments where API costs limit retries, this first-attempt reliability can inform developers beyond the aggregate success rates.

Near-miss analysis reveals specification precision challenges

Standard benchmarking often treats task resolution as a binary outcome, classifying runs as fully correct or fully a failure. However, per-test analysis in IDE-Bench reveals a common outcome of "near misses," where the agent implements the core logic but fails a small number of tests due to failing to adhere to output formatting or due to edge cases.

This illustrates a recurring pattern in agentic coding: specification precision may be more challenging than algorithmic correctness. An 8.3% gap in tests (as seen in Event Callback System Task-4 for Sonnet, Opus, and Gemini 3 Pro) can correspond to a disproportionate amount of engineering effort, as the remaining work is often small but brittle (such as formatting, ordering, or off-by-one behavior). These "failures" are not complete failures. It may be more efficient to manually correct rather than fully regenerating from scratch.

Efficiency = pass@5 / (Tokens/1000) — Higher is better

→ Efficiency Score = pass@5 / (Tokens/1000)

Success rate and computational cost do not necessarily correlate: Grok 4.1 Fast is the most token-efficient model (67.50% pass@5 at 182k tokens per success; efficiency 0.37), while Claude Opus achieves strong coverage (86.25%) but at a much higher cost (1,354k tokens per success).

These results help us distinguish between two different refinement styles: "fast" vs. "thorough." Models like Grok 4.1 Fast and DeepSeek R1 tend to be cheap when they succeed; however, they succeed much more rarely. On the other hand, models such as Claude Haiku and GPT 5.2 succeed more often, but their successful runs are more expensive due to longer iterative trajectories.

Thus, we propose a two-tier routing architecture, where a faster, efficient model does a first pass, followed by a more thorough model for fallback.

How models perform across different tech stacks and languages

Token usage and success rate visualizations

.png)

.png)

.png)

Analysis of common failure patterns across models

.png)

Early action dominates failure. Among failed runs, the most common failure modes are Premature Editing (63.0%), Thrashing/Backtracking (28.2%), and Context Loss (27.6%).

Open-weight failures skew toward "act too early." Open-weight and lightweight agents exhibit extremely high Premature Editing rates (80-95% of their failed runs), suggesting they begin patching before they have a correct map of the codebase. This is consistent with failure trajectories where early edits trigger downstream instability rather than convergence.

Frontier failures skew toward non-convergence. Several frontier and mid-tier models show disproportionate Context Loss and Thrashing when they fail (e.g., Claude Sonnet has 74.6% Context Loss among its failed runs; Grok 4.1 Fast has 69.7% Thrashing), indicating that failure often comes from unstable convergence under longer tool loops and not from total inability to implement the core fix.

Failure modes concentrate by stack. Tool Call Failures are disproportionately concentrated in the Java web repository and the full-stack translator (together accounting for roughly 52% of Tool Call Failures), while Syntax Error Loops are concentrated in the Python-heavy repositories (network-traffic-analyzer and code-quality-analyzer together account for roughly 82% of Syntax Error Loops). This suggests that brittleness in workflows is not uniformly distributed across domains.

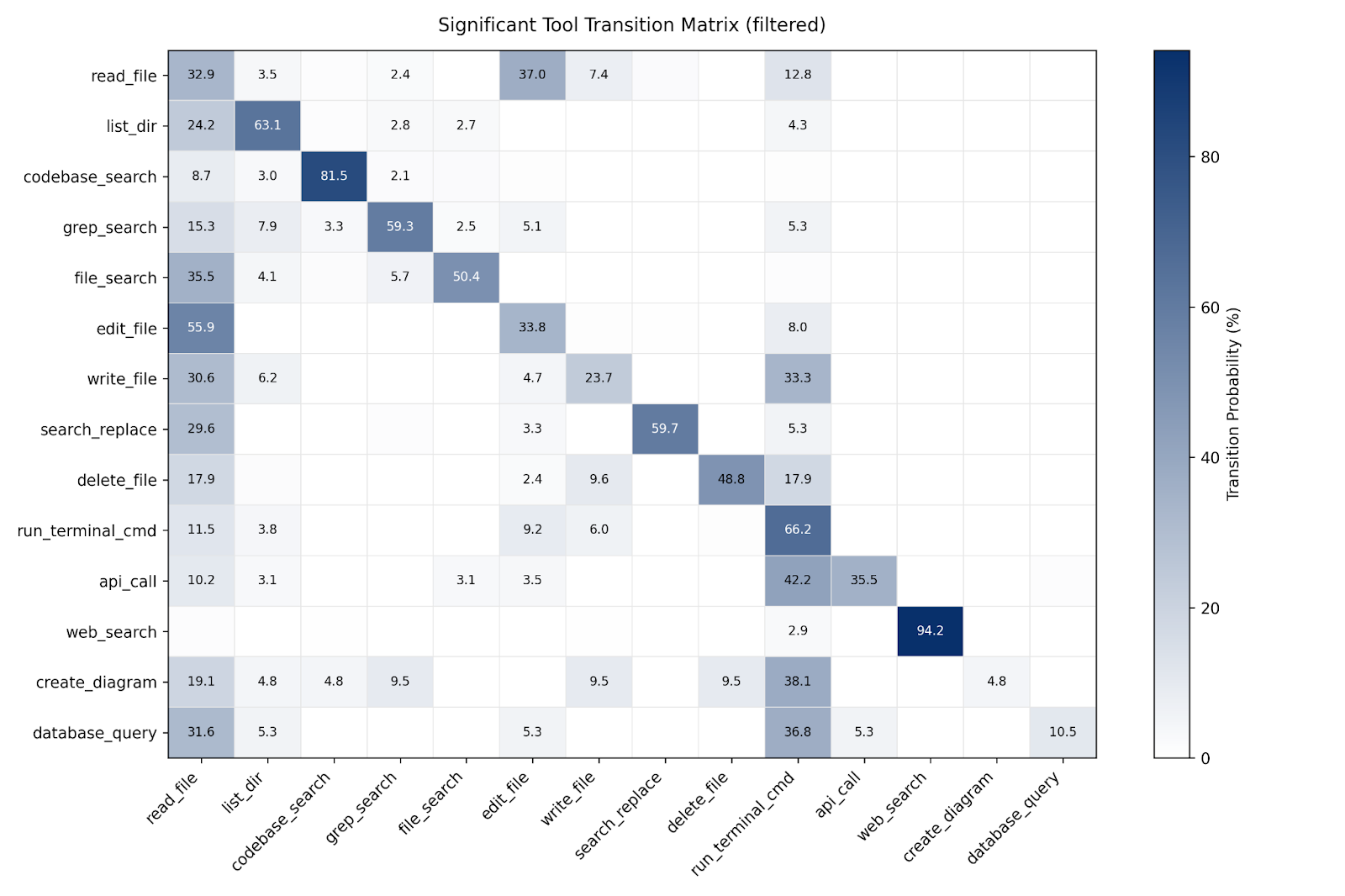

Tool usage patterns and transition probabilities across models

We find that tool sequences are not random, but follow patterns.

Read-edit alternation is the core loop. After read_file, agents transition to edit_file 37.0% of the time, and after edit_file, they return to read_file 55.9% of the time. This suggests iterative local reasoning rather than one-shot patching.

Tool usage is self-chaining. Search and execution tools self-chain at high rates, reflecting refinement loops: codebase_search→codebase_search 81.5%, run_terminal_cmd→run_terminal_cmd 66.2%, list_dir→list_dir 63.1%, grep_search→grep_search 59.3%.

Edits are rarely followed immediately by tests. Only 8.0% of edits transition directly to run_terminal_cmd, implying that many agents re-check context before testing (often by reading or searching first).

These signatures line up with the failure taxonomy. Short-circuiting the read phase is consistent with Premature Editing, while repeated self-chaining without a stabilizing read/test cycle aligns with Thrashing/Backtracking and longer-horizon Context Loss.

.png)

Deployment Recommendations

- →Production-Ready Threshold (85% pass@5). Our retry benefit analysis reveals a natural threshold at 85% pass@5 that separates production-ready models from those requiring multiple attempts. Models above this threshold (GPT 5.2 at 95%, Claude Sonnet at 88.75%, Claude Haiku at 87.50%, Claude Opus at 86.25%, GPT 5.1 Codex Max at 85%) show minimal gains between pass@1 and pass@5 (1.25–11.25 points), indicating stable, first-attempt success. Models below 85% exhibit dramatically higher retry bene- Fits, DeepSeek V3.2 gains 40 points (31.25% →71.25%), Grok 4.1 Fast gains 32.5 points (35% →67.5%), reflect- ing inconsistent, iteration-dependent behavior unsuitable for production where developers expect deterministic results.

- →Single-Model Deployments by Objective. For maximum task resolution regardless of cost, GPT 5.2 (95.00% pass@5) represents the optimal choice. For cost-sensitive deployments, Grok 4.1 Fast achieves the high-est efficiency score (0.37, computed as pass@5 / tokens per success in thousands) while maintaining 67.50% coverage. Production environments requiring consistent, predictable behavior favor Sonnet (σ = 0.045) or Opus (σ= 0.027) over higher-variance alternatives like Gemini 3 Pro (σ= 0.191) or DeepSeek V3.2 (σ= 0.323). For first-attempt reliability (pass@1), Claude Sonnet leads at 87.50%, followed by GPT 5.2 at 85.00%.

- →Language-Specific Routing Sonnet, Opus, and GPT 5.2 perform the highest, respectively, on tasks regarding C and C++ systems and tooling. GPT 5.2, Opus and Sonnet perform the highest on TypeScript/Node.js services, respectively. Opus, GPT 5.2, and Sonnet, perform the highest on Python data analysis. GPT 5.2, Gemini, and Sonnet, perform the greatest on Java web tasks, respectively.

- →Two-Tier Architecture Strategies.

- →Fast-then-thorough: Deploy Grok 4.1 Fast for initial attempts (covers 67.5% of tasks at high efficiency 0.37), falling back to Claude Haiku for unresolved cases. Empirically, the union solves 71/80 tasks (88.75%), while reducing computational costs for the 67.5% of tasks that Grok resolves without requiring the more expensive fallback.

- →High-coverage pairing: GPT-5.2 for initial attempts (95% coverage), falling back to Claude Sonnet for failures. The Jaccard index of 0.909 indicates high overlap (90.9% of tasks solved by either are solved by both); empirically, the union solves 77/80 tasks (96.25%), with incremental gains concentrated in the Java web repository where success is less uniform across models.

- →Reliability-aware pairing: Claude Opus 4.5 (ICC=0.804, highest reliability) for production tasks requiring deterministic behavior, with GPT 5.2 (ICC=0.493, moderate reliability but 95% pass@5) as fallback for tasks where Opus reaches iteration limits. This leverages Opus’s predictability while achieving high overall coverage.

- →Avoiding Redundancy. Claude Haiku and Claude Sonnet exhibit 93.2% Jaccard overlap, the highest among all pairs, indicating heavy redundancy; their union solves 73/80 tasks (91.25%). Similarly, GPT-5.2 shows 89.6% overlap with Claude Haiku and 89.5% with Codex Max. For cost-effective coverage, pair models with lower Jaccard indices (e.g., Grok 4.1 Fast and Claude Haiku), or accept high-overlap pairings only when optimizing for peak coverage rather than diversity.

- →Consistency vs. Exploratory Contexts. Production IDE assistance requiring predictable behavior favors Claude Opus or Claude Sonnet (low σ, high ICC). GPT 5.2 offers the highest coverage (95% pass@5) but exhibits only moderate reliability (ICC=0.493), making it better suited for settings that can tolerate more attempt-to-attempt variability. Research or experimental contexts can leverage Gemini 3 Pro’s higher variance (σ= 0.191, ICC=0.567) to explore diverse solution approaches, accepting occasional inconsistency for broader exploration.

Conclusion

IDE-Bench provides a full-stack benchmark for evaluating LLMs as containerized IDE agents and shows that frontier models can solve a large fraction of real-world engineering tasks. We evaluate whether an agent can reason, navigate, and use tools inside a containerized environment resembling real software engineering practice. The benchmark consists of 80 multi-file tasks spanning eight domains (systems programming in C/C++, enterprise Java web applications (Javalin/Thymeleaf), web services in TypeScript/Node.js, and data processing in Python, among others), and it measures both task-level success (pass@k) and finer-grained signals such as per-test pass rate, iteration trajectories, token usage, and outcome variance. Our evaluation revealed clear performance ceilings in specification compliance, reliability, and domain coverage. We find that our benchmark analysis indicates that single-number rankings are not enough, as LLM deployment evaluation must account for task specialization, cost, and consistency. We hope IDE-Bench serves both as a practical guide for current IDE integrations and as a set of concrete targets for improving the next generation of software engineering agents.

Read the full paper on arXiv

→ arxiv.org/abs/2601.20886